Making whatever adjustments necessary so you can do your work under less than perfect conditions is very millions.

Goya didn’t sit around waiting to have perfect lighting.

He mounted candles on his hat so he could keep painting as dusk fell.

I have some kind of vague sense that my desk isn’t quite right and that the not-quite-rightness prevents me from doing the work I fancy I’d do with a desk of slightly different proportions. Meanwhile, Goya is mounting candles on his hatband and painting directly onto the plaster walls of his own house. Here is Goya noticing that he can skip ahead a few centuries in his painting, “The Dog.

This dog is beset by landscape of modernist proportions, a shadowy hulking ghost figure, and a sloping ground that may engulf him at any moment, but he’s keeping his nose up in it all. “We do not know what it means,” Robert Hughes says, “but its pathos moves us on a level below narrative.

Yes, and this is another way of gesturing toward defining millions, to come to know millions by how it moves us: on a level below narrative.

Which is not to say that some stories can’t be very millions. Or that an encounter with millions is not somewhere at the heart of most stories.

When Goya brimmed his hat with candles, he wasn’t just lighting his own easel.

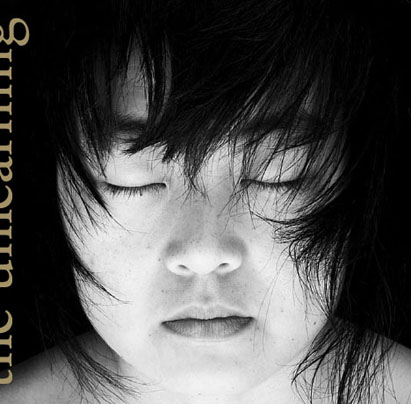

Here’s Theresa Wong’s song, Candlehat, from her new CD, with Carla Kihlstedt, The Unlearning,  inspired by Goya’s Disasters of War.

inspired by Goya’s Disasters of War.

Here’s a drawing of Goya by a fifth grader in Darien, CT.