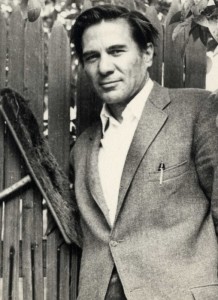

This afternoon before I heard from a friend that Galway had died, I was writing to another friend about a 2,000-year-old date palm seed that germinated in 2005 and is now a tree. Now I am thinking of how that date palm seed feels kindred with Galway’s way of inhabiting time, how his poems have folded within them so much life force.

This is a tribute to Galway I gave at a reading in 2004, in honor of of his retiring from NYU. I’m going to just include it here, as I wrote it, in the present tense.

(2004, New York University)

I’m honored to speak on behalf of Galway’s students.

There is a Sanskrit word “kalpa” that seeks to contain the idea of “an endlessly long period of time.” One definition reads, “Suppose that every hundred years a piece of silk is rubbed on a solid rock one cubic mile in size. When the rock is worn away by this, one kalpa will still not have passed.” Given such a span of time to convey the gratitude and love Galway’s students feel for him, my account might approach adequacy: I have three minutes.

Given a kalpa, I’d catalogue how Galway’s work was my teacher long before I entered his class. I remember startling at his poem “Prayer”

Whatever happens. Whatever

what is is is what

I want. Only that, but that.

First: the thrill of those three contiguous “is’s.”

Then: what if I could actually embrace it all? I wanted a loophole, but still it was an experiment I was poised to try, and the poem became a tuning fork for my intention.

To paraphrase Robert Motherwell on teaching painting, “Poetry cannot be taught but it can be learned.” This configuration relies on the rare teacher, like Galway, whose simplest gesture models a way of being in the world, what I call a “deep-tissue teacher.” It’s not that something’s given to you from outside yourself. In the presence of a person radiating human potential, suddenly, epiphanically, or maybe it’s more gradual, you become aware of the opulence of your human life, of your interconnection with all things animate and less obviously animate. And by that example, you feel mobilized with responsibility.

What is this responsibility? All week, thinking of what Galway’s example urges, I’ve had in mind a haiku written by the 18th century Japanese poet Issa after the death of his daughter.

This world of dew

is only a world of dew –

and yet, and yet.

Each of Galway’s poems articulates the intention to love in the full knowledge of impermanence. Each line risks this “and yet.”

To bring a poem into Galway’s field of attention is to watch it fluouresce where it is most alive. He always reads toward the freshest locution, pinpointing, with a firm delicacy, where habit has set in, where fondly held delusion occludes the poem, kindly noting where the poem veers “poetical,” a graver offence than mere dullness.

And there is his unimpeachable pragmatism: I showed him a two-line poem I had called “Couplet”– I had my reasons – He said, “Even at quite a distance we can see that this is a couplet.”

Galway senses, surgically, something as yet unexpressed within the poem and helps to coax it into language. In critiques he would stabilize an insight a student had come to already, and the student inexorably, with each week, came to inhabit his or her voice with more verve. Shao Wei wrote, “Galway helps me sing in English.”

“There is no work on the poem that is not also work on the poet,” he told Kathy Graber. A hallmark of Galway’s teaching is his capacity for bearing witness, for seeing some essential aspect of a student’s nature that perhaps no one had ever seen, or maybe it had been seen, feared, and suppressed. To quote “St. Francis and the Sow, “Sometimes you have to reteach a thing its loveliness.” Once you’ve been received this way, it becomes more possible to find footing in the often terrifying groundlessness of each new poem.

Some student snapshots: Galway seen from across Washington Square, white shirt billowing; white shirt blood-soaked at the Selma Marches; Galway on retreat spending the night in a shed, coming to breakfast animated in the thrall of a first draft of “The Deconstruction of Emily Dickinson;” building a driftwood shack at Race Point beach; expressing enchantment with the fax machine as a tool for sharing poems with friends.

Galway emanates what Yeats called “radical innocence.” Susan Brennan dubs it “A Galway state of mind,” the curiosity of someone perpetually new to the scene. I once heard him say the word “videographer” in a comment between poems at a reading, and I could overhear in his voice a trace of the first human being ever to put syllables together to form a word.

Short a kalpa, I’ll close now and say simply, Thank you Galway, and borrow another of your lines, thank you for hearing us into shining.

I completely loved your piece on Galway who is someone I did not know. Now, I know a little bit more and I’ll seek him out.